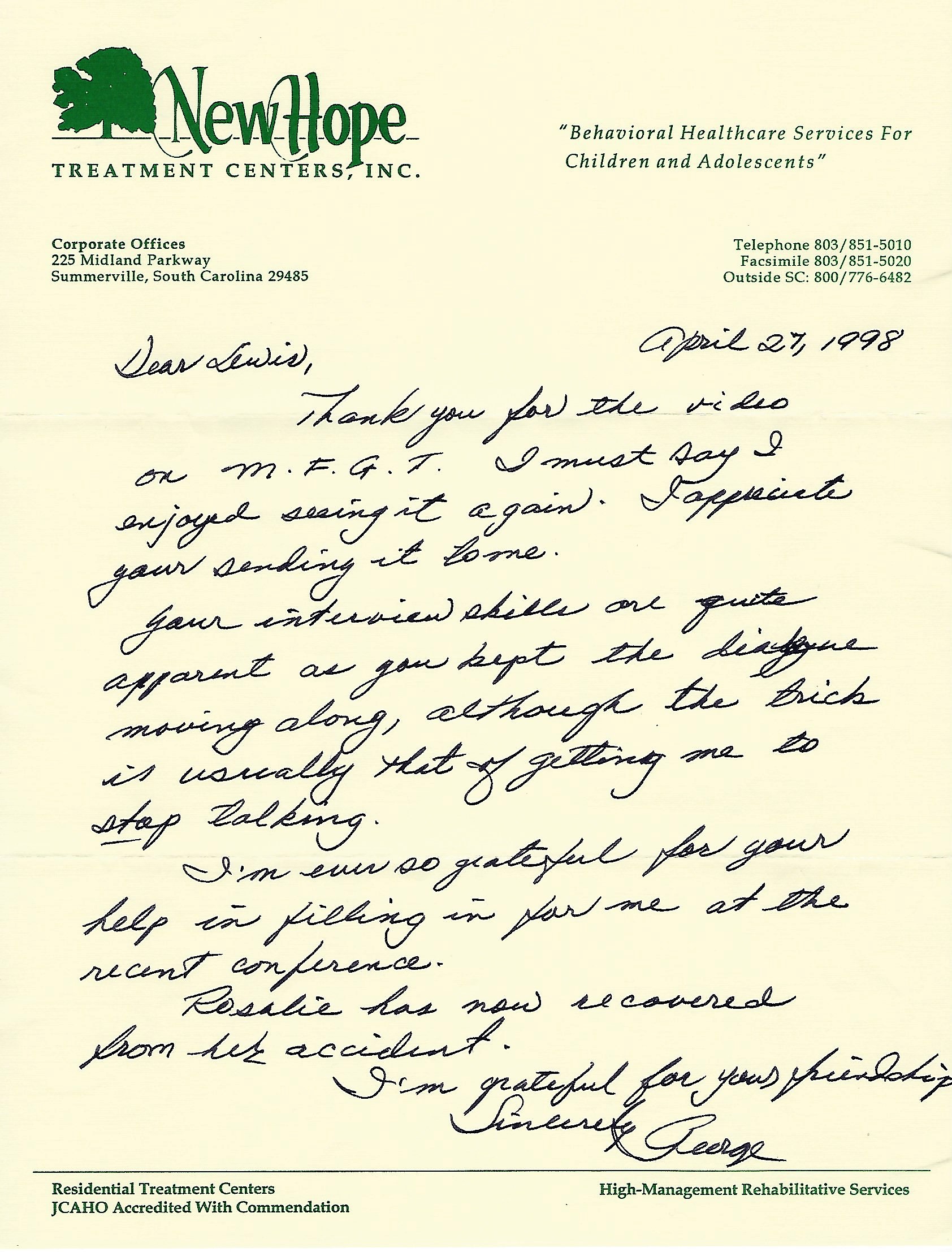

An Interview With the Father of

Adolescent Multiple Family Group Therapy,

George H. Orvin, M.D.

Transcript and Video Links

ã1994 By

Lewis N. Foster

(Note: Two videos of George H. Orvin, MD are on www.youtube.com)

https://youtu.be/t9WybAUA2Js

George H. Orvin, MD, Interview on Adolescent Psychology and MFGT 1994 about

2 hours.

https://youtu.be/oMqjCIACaNY

George H. Orvin, MD. "Presentation on Human Life" at the Annual SC

Conference on MFGT 1994 38 mins.

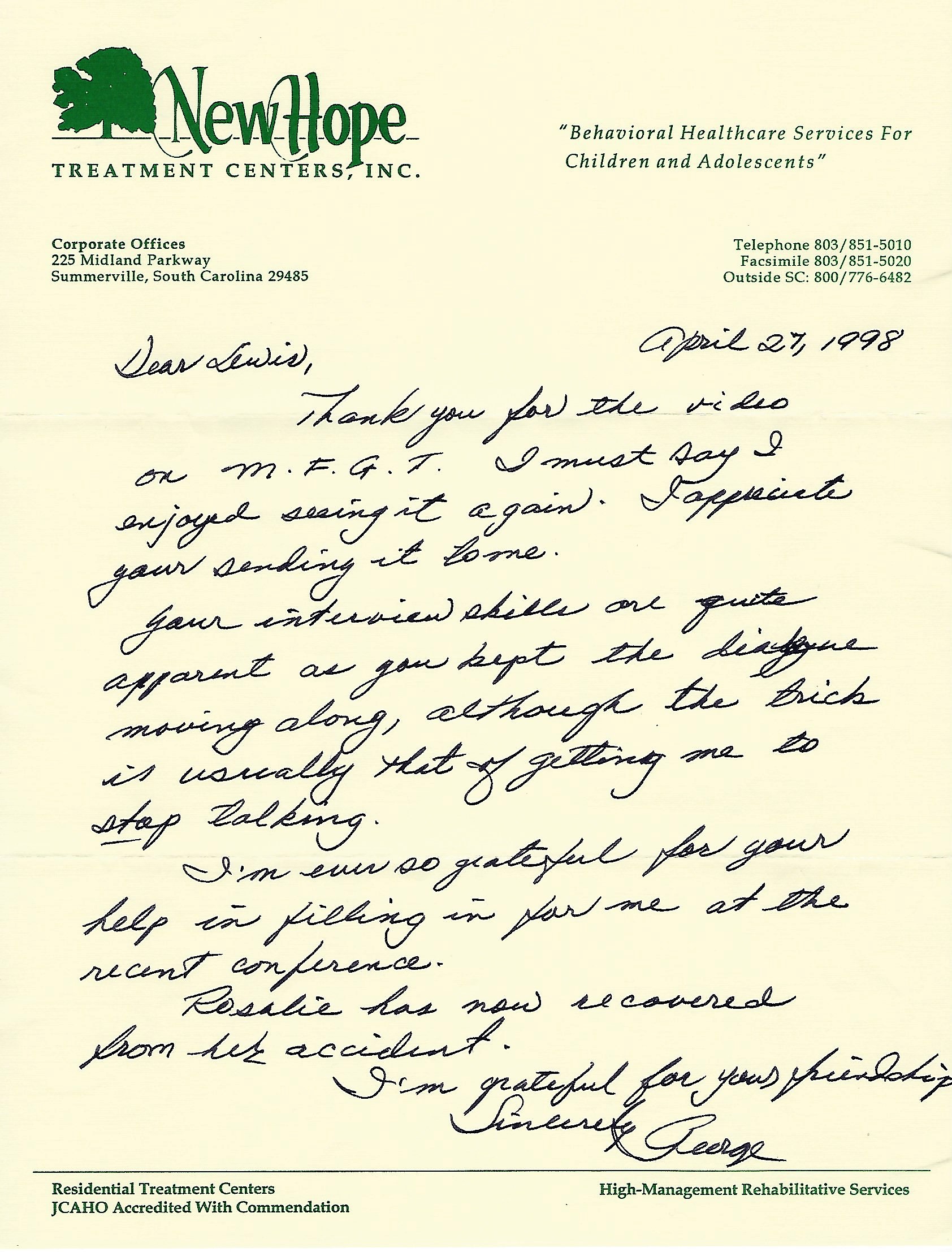

George Henry Orvin, MD "Father of Adolescent MFGT" August 6, 1922 to

August 29, 2014 Charleston, S.C.

On March 14, 1994, Lewis N. Foster, the Founder of the Multiple Family Group Therapy Resource Center

talked with Dr. George H. Orvin, a Psychiatrist specializing in the

treatment of adolescents. Dr. Orvin

is recognized as the Father of

Adolescent Multiple Family Group Therapy. In this interview he

talks

about his model of therapy with adolescents, as well as

his working with families in multiple family

group

therapy. Dr. Orvin has been doing multiple family group therapy for three

decades. He is the

Founder and Chairman of the Board of New Hope

Treatment Centers.

Dr. Orvin: I tell a story about the Pope. It's about a

man who

spent his life tailoring clothes and when he retired he

told his

friends that arrangements had been made to have an

audience with

the Pope in Rome. They flew him over and paid all of

his

expenses and he had a private audience with the Pope.

This

fellow had spent his life doing nothing but making

clothes for

men. He was thrilled to be able to meet the Pope and

when he

came back all of his friends were eager to find out

what it was

like. They said to him "Tell us what sort of a man is

the Pope?"

He said he was a 37 regular. Tailors do that, they see

people

according to their view of the world. Psychiatrists do

that.

People in the Mental Health field do that. We bring

certain bias

to our work and that influences how we think and how we

manage to

deliver care. So it helps if people have some idea

about that.

L. Foster: Are you be willing to say how Dr. George

Orvin got to

where he is today, maybe a resume'?

Orvin: Sure, it's all a part of truth in packaging.

I would

sort of alert you to the fact that, first of all I am a

physician. Because of that I view so much through the

eyes of a

physician. I can't help that. I have been trained in

medicine

and that is what I am supposed to do, see problems as a

physician. Secondly, I am a physician who deals with

mental and

emotional disorders. I am a psychiatrist. Because of

that, it

causes me to look at problems as psychiatrists do. On

top of

that, I am not just a psychiatrist but I am an

adolescent

psychiatrist. Now let's clarify, I am a psychiatrist

that treats

the adolescent rather than a psychiatrist who still is

an

adolescent. I am a psychiatrist who specializes in the

treatment

of the adolescent. All of those things conspire to

influence

what I think and how I manage to become the conduct of

my career.

On top of that, I am a husband, a father and I am a

grandfather.

All of those things have had their influence in shaping

the way I

view the world. So having spent ten years in general

practice,

it's hard for me to forget all those things that I

learned in the

bosom of a family that was having some sort of medical

problem.

I found that I was spending a lot of time with

families. When I

would treat a family in general practice, before I went

into

psychiatry, I found that periodically I would sort of

run behind

schedule. And low and behold, it was always because

the patient

had some sort of emotional problem, something other

than his cut

finger. I would get so engrossed in what was happening

in that

person's life that I would lose track of time and run

behind

schedule. I finally decided the best thing for me to

do was to

get trained properly. I was practicing psychiatry

without a

portfolio and I needed the training so I went back.

Closed my

practice in Charleston and went back to the University

and spent

three years studying Psychiatry there and then took

another year

at the University of London and spent a little over a

year there.

Then came back and joined the Medical University where

I taught Psychiatry.

Foster: In Charleston?

Orvin: Here in Charleston, at the Medical University

of South

Carolina. I taught Adolescent Psychiatry. I started

in l961.

In l967 I limited my practice to the adolescent and was

given the

opportunity of setting up an all adolescent inpatient

psychiatric

service at the Medical University. At that time there

weren't

any adolescent psychiatry beds in the Southeast that

were

designed just for inpatient adolescent psychiatric

care. There

were eleven or twelve other facilities in the entire

country that

were university based and dedicated to the treatment of

the

adolescent. So we set up that program in the

Department of

Psychiatry at the Medical University and began an all

adolescent

service. Ten beds, that's all. My job at that point

was to

treat dysfunctional or sick adolescents, but that

wasn't the full

extent of my job. My job was to treat sick children.

It was

also to teach others how to treat sick children, which

added a

dimension to what we were doing that made the job more

fun, but

enlarged the challenge in that, at that time, there

wasn't much

in textbooks about the adolescent. Child psychiatry

was fairly

well established at that time and child psychiatry took

care of

the adolescent when they had to, usually against their

wishes. I

recall flipping through some of the charts and some of

my old

books when I began working with adolescent's. I would

go back to

the word 'adolescent' and sure enough they would have

two

references in the old book and juvenile delinquency

usually was

what it was about. So at that time there was really

nothing that

you could prepare yourself adequately for. So I

learned about

adolescents by groping in the dark. I and my staff

began to

learn some things about treating the adolescent. The

thing that

I learned, first of all, quickest, was the most

powerful

recuperative force in the treatment of dysfunctional

children.

It is the bosom of that child’s' family. The family is

supposed

to do three things. The human family is to produce and

autonomize children. New recruits for the future.

Society looks

to the family for that and they look to parents to

indoctrinate

these replacements and get them ready for when they are

needed

when other parts of society die off and the new

recruits are

coming on. The human family is supposed to create

children and

autonomize them. Raise them up, that is number one.

Number two,

the human family is supposed to provide for the care,

the

physical safety and the physical needs of it's

members. And

thirdly, the human family is supposed to stabilize and

fulfill the development of the personalities of the

parents.

Family is the place where children grow. The family is

also the

place where adults are supposed to grow. It is in that

context that

we find dysfunctional children. We find them in

families that

are struggling, struggling to keep their heads above

water.

If we want to understand the child and the problems

that he is having,

we must of necessity, thoroughly understand the context

in which that

child is struggling. What is going on with this child

is a very legitimate

question. What are the barriers he is encountering,

but also what is

going on in that family.

Foster: So you are thinking in systems already?

Orvin: Absolutely. And that is the system. You

think of the

family as a system, it has it's own boundary, it has

its own

location. It has its way of communication. It has its

feedback

groups and it touches on other systems ‑ the

educational system,

the occupational system, the governmental system, the

religious

system, and other families and other systems. So I

think in

understanding what's happening with families, we need

to have

some understanding about what is it that families are

supposed to

do. Not just really the general responsibilities but

how do

families change, what are the things that happen

within families

and how do those events influence the growth and

development of

this particular child. But also, how does events

influence the

growth of the people who are taking care of this

particular

child.

Foster: In l967 you put families together in

multiple family

therapy groups. I understand that this social

setting has

significant impacts on individuals and the families.

Orvin: Absolutely. I sort of fell into multiple

family group

therapy. I didn't know anything about it, nobody else

did. Only

one or two other people in the entire world were doing

anything

like that. Peter Laqueur, up in Vermont, was bringing

together

families of adult schizophrenic patients. I didn't

know he was

doing it. When I organized the adolescent inpatient

service I

had ten beds and ten children. We notified those

children's

parents that we were going to have an all adolescent

service.

They came to learn some things about what to expect. I

would

have a room a little bit larger than this one, three

o‑clock on a

Friday afternoon, and I spent a hour telling them what

they could

expect. They sat around in chairs and I sort of

explained things

to them. Then the hour was up and they were ready to

pick their

children up and I had completed all that I wanted to

tell them,

so I said we will meet again next Friday and I'll

finish up. So,

the next Friday we met again and I was going forth with

some

ideas about what we were doing and what the adolescent

services

was going to be like. I made a statement. I said,

"You know,

all parents love their children". One of the fathers

snatched off

his glasses and said, "Well let me tell you something.

If I've got

to come here every week and listen to garbage like

that, count me out,

I don't want any part of this silly thing" and got up

and walked out

and slammed the door behind him. Well, there was a

silence.

Some nervous clearing of throats. I was, it's hard to

believe,

at a loss for words, but I managed to finish it out and

said to

the group that we would meet one more time; next Friday

will be

the last. The next Friday we gathered together again

and, lo and

behold, there was the father of that boy that had

stormed out.

I began to sort of give my little explanation to the

families about

what we were going to be doing and he said, "Wait a

minute before

you get started, I have to apologize. I'm sorry that I

said what

I said and I am embarrassed by the way I behaved and I

want to

apologize to all of you here. I hope you will forgive

me for that".

I started to say something and he said, "You know, when

I was a

little boy, my father abandoned me and my mother when I

was seven

years of age. Then my mother and I lived together for

a year and she died.

I was taken by members of her family and his family. I

spent the rest

of my childhood going from pillar to post and it was

terrible, it was awful."

He began to weep and he began to shed tears about it.

One of the

mothers in the group said, "Now hold on Mr. Smith, let

me tell you,

yours' sounds a good bit like my childhood except I was

a little bit

older when it happened to me and I had the same kind of

experiences

until my maternal aunt offered to take me in". She

talked to him

and he listened to her. Another parent chimed in and

offered some

advice. I was standing there listening to what was

happening and

watching the interaction between this distressed man

and these

comforting people. It suddenly struck me, my what a

powerful,

powerful instrument this is. We've got something

valuable here.

We finished up that session and in May of l989 {over

two decades}

I was still holding that Friday afternoon session

for families. Because,

what we had done, we had created a family of families.

You see, a

family really is a psycho logic support system designed

to sustain

its members during periods of adversity. Think about

that. A psycho

logic support system designed to sustain its members

during periods of adversity.

Home is where the wound is healed. The balm

applied. And here I have

a system of systems, a group of families and they were

applying the balm

and they were helping to heal all these wounds.

Someone has said that

marriage itself is an attempt at healing. We get

married for various

reasons and a lot of times we get married to make life

better. If I get

married everything will be all right. But here these

families came

together and I quickly saw that this was something that

was very powerful.

I could get Mr. Jones to talk with Billy Brown. The

families would sit in

chairs and the room wasn't big enough, I never wanted

the room that is

big enough. Don't ever do multiple family group

therapy in a room that is big enough.

Foster: How come?

Orvin: Don't ever have a party in a room that is too

big.

Make people sit close to one another. Make them touch

one

another. Don't scatter them up. You do what you can

to enhance

the intimacy of that experience. I never would have

enough room

or enough chairs. The kids would come in and flop on

the floor

and the parents would sit in the chairs and I would

conduct group

therapy for fifty people. Aunts, moms, dads, brothers,

and

sisters, an occasional uncle or grandmother,

grandfather, and do

multi‑family group ‑ one hour ‑ once a week. I could

get Mr.

Jones to talk to Billy Brown and Billy Brown could not

say,

"There goes my old man again ‑ treating me like a

little boy" ‑

the dependency issue would be short circuited. Mr.

Jones can say

things to Billy Brown that Mr. Brown has already said,

and it

went in one ear and out the other. His son had to

prove that he

wasn't daddy's little boy anymore. I've had men in

group, and

father's in my group, listen to a new arrival. "Well

yes, we're

here, and we're unhappy, our daughter has been doing

this and

doing that and doing the other. My wife and I are just

worried

to death and we want to do something to get her

straightened out"

and so on and so on. I've had an old veteran of the

multiple

family therapy group sitting in there. He starts

shaking his

head and he says "You know, you sound a whole lot like

me".

"What?". "Yeah, you sure do, I brought my daughter in

here six

months and I've been coming to this thing ever since

then and I

said the same things you were saying. I was just here

to see

about helping my daughter". And he said "You are going

to find

out that you are going to help more than your daughter

and you

are going to find out that you can benefit from what is

happening

here. Let me tell you what is happening in my family

with me and

my wife." And then he would talk and help this

newcomer

understand that we are all struggling.

Foster: He could see where he came from and the

newcomer had a

place to go.

Orvin: That's right. And we always had a family

that would

leave at the end of the treatment, take their child and

go home.

We made them come back for six more sessions because

it's

different back there. We wanted people here to see

that you do

get well and someday you do leave and so they could

come back and

offer some encouragement.

Foster: That was continuing care.

Orvin: That's right and not only that, as they were

struggling

to make their adjustment back in the real world, they

could file

in their mind, "Well, I want to talk about this when we

go to

multi‑family group next week, by golly, she did this,

and he did

that, and I'm going to see what the rest of the group

says". And

they would come and bring up circumstances that had

arisen in

their home and we would talk about that. There are a

couple of

things that are important about multi‑family group.

One of my

favorite rules is that nobody has to talk. You don't

have to

talk. You have to come but you don't have to talk.

It's hard to

talk. People freeze up and a lot of times if you don't

have to

do it, it's a lot easier. So sometimes one group

member would

say, "What's the matter, you never say anything, you

ought to be

contributing something". Because sometimes that

particular

person will be helpful by saying one or two words. So

that, in a

multi‑family group I try to avoid the suggestion that

you've got

to contribute a certain number of words each time.

Certainly you

have to kind of use yourself as a therapist and lend

some of your

strength to this one and then to that one and then to

the other

one and to that one. When I began my training, my

supervisor,

helping me to learn about psychiatry in the late

fifties, and I

were doing couples therapy, family therapy and we had a

patient

who was depressed. We were at the hospital and we were

treating

her and she had talked to me about the problems she was

having

with her husband. So I told my supervisor that I would

call her

husband and the three of us were going to sit down and

talk. And

he said "Don't do that". And I said "What do you

mean?", and he

said "If you try to do therapy with your patient and

you bring in

her husband, you are not going to do any therapy,

you're not

going to be a therapist, you're going to end up as a

referee".

And that made a little bit of sense. I understood

that, but I

said "I'm going to do it anyhow". And I went ahead and

did it

and he was right, they were going at one another. Here

I am

refereeing. It struck me that the one thing a referee

must do is

to make sure he isn't on one side all the time. He

needs to blow

the whistle when the blue team gets off and he needs to

blow the

whistle when the red team gets off base. As a

therapist I began

to develop that skill to be able to have this person

angry and

upset and to keep this person from terrorizing this one

and to

help this one understand some of this but at that

particular time

we weren't doing anything like multiple family group

therapy. So

as a therapist I did that for thirty years running a

multi‑family

group. One needs to use ones position as that powerful

figure to

bring some protection and to strike a posture of

understanding.

One of the parents listening to things we were talking

about in

the early days was coming in wearing sun shades in the

group, he

pulled them off and said, "You know, you are always on

the side

of these kids. You never think about us." He was

giving me a

hard time about it. That didn't sound like good news

to me, it

didn't make me feel real good but I stopped and thought

this man

needs to be able to say some things. I then realized

he wasn't

going to jump up and come hit me so I helped him. I

said to him,

"I think maybe you're right. We probably make some of

those same

mistakes you'll make. You know they are important to

us and

sometimes we get so caught up in their problems that

maybe we

overlook the problems that you folks have."

Immediately somebody

in the group came to my rescue and said, "Wait a minute

there.

You know you are wrong; I've been in this group for

such and such

time and...," I would love to have some controversy.

I would

never try to stamp it out. I would give it some air

and let it

grow because invariably you are going to find somebody

else is

going to jump in and help take part in that.

Foster: When you are starting a multiple family

therapy group,

do you have a way of joining with the group, of having

everybody

introduce themselves and are there some stages to a

group

session?

Orvin: I didn't make people wait. If you had a

child in my

care, you came into the group right away. What we

would do with

new families is have them say who they were, and then

each person

in the group would say like "I'm Harry Jones, this

little

red‑haired boys daddy". Mama would say, "And I'm his

wife, I'm

Helen" and I'm this, that and the other. "We've been

here for

about three months and we've been pleased with what's

happened".

They would go around and do some kind of Welcome Wagon.

That is

what I called it. I'd send out the Welcome Wagon and

they would

welcome this new neighbor who just moved into the

neighborhood.

They would tell them where things are, where the

grocery stores

were, the dry cleaners and all that. They would tell

what this

neighborhood is like. Then the new family would say,

well I'm so

and so and she is so and so and this is our daughter so

and so

and we've been having these kind of problems. They

would talk.

Foster: Would you move from the Welcome Wagon to

problem

definition?

Orvin: That's right.

Foster: And from problem definition, maybe into

everybody

interacting with everybody else.

Orvin: That's right.

Foster: And the leader himself becomes less central.

Orvin: That's right, and it's delightful to have a

nice one or

two folks ‑ I had one woman who was in my unit and she

was there

for maybe six months. He (her husband) was there for

every

session and he was there for five years after she left,

he kept

coming. He was able to get something out of it every

time he

came. So, yeah, I would have them say what they were

up against,

and would offer to the new families some word of

encouragement,

but I would then say, "You all make it sound so nice

and easy and

it isn't nice and easy. Tell them about what happened

on so and

so". Well, yeah, then they would lay out one or two of

the

problems they had had in the group or in the hospital.

Foster: Laqueur had a name for what you were doing.

He called

that type of leader an Orchestra Conductor. You would

focus on

the process, direct, and they (the families) would add

the

content.

Orvin: Absolutely, I orchestrated it. I would bring

in the

woodwinds and sometimes I would bring in the brasses

and I knew

what my musicians were capable of doing. I knew where

I could

go. I had one member I could just look over there and

wouldn't

have to say anything and he would start. I learned

some

wonderful things from those people.

Foster: If I understand correctly, your assessment of

these

families actually took place in the multiple family

therapy

group.

Orvin: Oh, yes! I could bring a child into my

office,

interview that child for thirty minutes, interview the

family for

thirty minutes and at the end I would know exactly

what's wrong.

The early mistakes were that I thought that because it

was

apparent to me, that it must be apparent to them too,

and its

not. I could assess them in that first hour and I

could pretty

well conclude what was wrong and what needed to be

done. The

problem was it took months to get done. I'd devise a

plan about

what this family’s' needs were and how to go about

helping them

learn those things. I could quickly see what was

wrong, but I

could not quickly get them to change their fundamental

approach

to one another. It is a slower process. Multi‑family

group is

really like a neighborhood where people visit over the

back fence

and lolly-gag with the neighbor next door and talk

freely with one

another. Of course in every little neighborhood you've

got one

family that sort of withdraws, sort of stays to

themselves. It is

helpful to liken that multi‑family group to a small

neighborhood. You have to understand that these folks

feel

isolated here because they feel isolated out there.

Out there

isn't going to do anything about it, in here we

should. First of

all we must be sympathetic as to why they feel that

way. And to

recognize that they do, whether they should or should

not, they

do. You need to have some kind of plan to help them

cope with

and bring those folks in to the bosom of that

multi‑family group.

Foster: The dysfunction that is taking place in the

family can

be defined as social dis‑ease and multiple family

therapy group helps

bring them back into social balance.

Orvin: That's right. The Chinese used to have block

meetings.

Everybody who lived in that particular block in that

neighborhood

would get together periodically and they would solve

neighborhood

problems. There were a lot politics involved and all

that but it

was sort of a neighborhood policy in a sense. We don't

have

sovereign prospect of treating the neighborhood but you

can, you

can blend together a group of people. Let me tell you,

I had a

diverse group, I had a commanding general in my group,

I had

people who were on Welfare.

Foster: How did you get the General to leave his

General role

outside the door and bring in dad and husband?

Orvin: That was the trick. It's really odd what

comes in. I

remember his daughter snuck off the unit and left, it

was an open

unit. When the general found out, he was down there

with his

adjutant in less than an hour and he confronted me in

my office,

and said, "What in the world are you going to do?." He

and I

were on good terms and I said, "Well, what have you

done?" He

said he called out a search and he'd gotten the police,

and what

are you going to do? I said, "I'll tell you what I'm

going to

do, I'm going to try to do whatever it is you don't

do. I'm

going to try not to do the things you do. Your

daughter is in my

care right now partly because of the relationship that

exists

between you and her and her view of you as a general.

I want her

to get to know you as daddy. So, Harry, I'm not going

to do what

you want me to do. I'm going to do what I think is

best for your

daughter. It is your privilege to leave her under my

care or to

remove her." He left her, because, even under all

those stars he

was a good father and it took him some time, but he was

able to

help her get in touch with that part of him.

Foster: That same situation exists with physicians.

They want

to come into multiple family therapy groups, for

example,....

Orvin: ....and bring their stethoscope with them.

Foster: Right, right. Any suggestions?

Orvin: Sympathy. I had them in my group, you know.

They were folks who wanted to be helpful and they

wanted

me to talk with them a little bit about what the blood

count

and what the electrolyte balances were and what

category

of medications were being used. Most of all, they

wanted

us to get along and they wanted to not feel incompetent

and to not feel inadequate. For some it was

embarrassing.

They are like everybody else, and you have to be

patient with

them and understanding. Without being truculent, you

have

to do what you think is right and you have to recognize

that

that child is my patient, but she is not my child.

They have

the right to withdraw her from my care and to do that

without

my being offended by it. It was my job, I thought, to

let them

know about the risks involved in leaving the treatment

setting

and to say to them "I think that's a mistake. I think

you are

making a mistake if you do that". But I wouldn't get

angry

with them; I wouldn't make them sign a release. I

wouldn't

try to protect myself legally because that means I

would

change the medical relationship to a legal one to say

"I think

you are probably going to sue me and I've got a piece

of paper to take to court."

It's what can be called defensive medicine. When

you start

practicing defensive anything, that is what it looks

like (George

puts up his fists). To me it looks like defense,

doesn't it look

that way to you? So that what we've got to do is to

say, "I

think it would be a mistake to do that, however, it is

your child

and at your insistence I will discharge her". I always

wrote in

the chart what I told them and I would always have a

witness

standing there listening to what I had told him. After

they

removed them, I would write up in the chart that I had

told them

I thought it was wrong. I told them why I thought it

was wrong

and I told them what I thought may happen. I would

sign that

with the date and time and my name and my head nurse

would come

and co‑sign it with me. And, my friend that will stand

up in

court. A piece of paper that says I am not responsible

is

duress, moreover, it's an angry patient mad at you. I

would say

to him "My advice is don't do that but that is your

child, take

her home, and I'll tell you what. I hope things turn

out the way

you think they are going to turn out and not the way I

do but, in

the event that things don't work well, call me. Give

me a call

and let me see what I can do to help." That's all

together

different from my telling him, "Sign this paper." So

those

participants in the multi‑ family group, you do

everything you

can to keep them participating in the treatment milieu

while

recognizing that those are free and independent people

and you

can't make them.

Foster: What do you think are the mechanisms of

change? What

do you think brings about change in people in multiple

family

therapy groups?

Orvin: First of all, fundamental rules apply to

individuals

and they apply to organizations. To bring about

change, the

individual must first of all believe that change is

needed.

Secondly, that individual must participate in the

process of

change. Thirdly, he must know that he can halt the

process

whenever he sees fit to do so. None of us will be

involved in a

process that says make me into what I ought to be,

change me in

any way you want and keep on doing it until you are

satisfied. I

might change but, first of all, I want to take part in

the

decision that change is needed.

Foster: If I wait for you to determine what I need, I

am going

to get less than what I need.

Orvin: Yes, that's right, and what I want to do is

to have you

tell me about how your life is going. To tell me the

good parts

and the bad parts, the things that are creating

problems for you.

I always know how to get kids to come into the

hospital, how to

get them to ask for help. I get them to talk about

their life

and how it was going. They wouldn't be seeing me if

their life

was going great. So I let them talk for about an hour,

telling

me about how terrible things are and I would put this

question to

them, I would say to them "Are you satisfied with the

way your

life is going?" Most of the time, it was the shake of

the head.

Next question ‑ "Do you want to do something about

that?" That's

what I call asking for help. Nobody is going to come

in and say

I am having all of these big problems and I want you to

help me.

Let them talk about how painful life is and find out if

they are

satisfied with that. "Do you want things to keep on

that way or

would you like to try to do something about that?"

Foster: People change when they arrive and accept

where they

are, and make a decision that they don't want to be

there. We

can't go where we want to go until we have arrived

where we are.

Orvin: That's right. They begin to try to change.

Even after

you have decided to try it is still hard and you might

need some

skilled help to be able to make that change. If you

are going to

change an individual or change an organization, that

individual

has got to participate in the discussions that change

is needed.

Secondly, they have got to participate in the decision

and then

the process of carrying out that change. Thirdly, they

have got

to know that they have the right to quit and to stop it

before it

gets out of hand. So, as a participant in a

multi‑family group,

we want people to come here and talk and share their

pain with us

and share their joys and things in their life with us.

Through

that process you begin to conclude that there are some

things

about your life that you don't like and that you would

like to

try hard to make some changes in your life and we'd be

glad to

help with that and we would be glad to give you an

agreement that

you can quit anytime you want to.

Foster: You are talking about helping people set

themselves

free, freedom.

Orvin: Yes, I used to make my adolescent patients

decide when

they are going to go home. Sometimes they would decide

too soon.

I don't argue with them. I say "You are going to stop

treatment?

You are the one that said, when you first came in, that

you

wanted to do something about the way you were getting

along with

your mom and that you wanted to do something about the

way you've

been getting along with girls in general. Now, you're

going to

tell me that the fight you had with Mary Ellen last

weekend, you

call that getting along? And you mean you want to keep

on doing

that? You want to stop trying?" I was always able to

persuade

them.

Foster: All of these points that you just talked

about can be

talked about in a multiple family group therapy

session.

Orvin: Oh yes.

Foster: In fact, when one family deals with it, every

family is

affected.

Orvin: I didn't have to be the one. They would say,

"Who are

you talking about?" You sat here last week and told

us all,

your mother sat right there and wept the whole time and

you're

talking now about doing such and such and so and so, I

think

you're making some progress, Billy, but you know, it's

crazy to

be leaving now. You look like your starting."

Foster: In an open‑ended multiple family therapy

group, you've

got people coming in and leaving and people are at

varying

points, so there is a legacy left with the group.

Orvin: That's right.

Foster: New families discover what they need to know

from the

families that have been in the group longer.

Orvin: That's right. There is a body of knowledge

that is

sort of accumulated over a period of time.

Foster: Are you in control of this body of knowledge?

Orvin: Observant of it and know how to orchestrate.

My job

was not so much to do it myself but to know how to get

somebody

else to do it.

Foster: Once you've got an ongoing group, it becomes

rather

easy for the therapist. What if you are just beginning

a group?

What are your suggestions?

Orvin: One of the things about starting a group is

to talk

about how scary it is and to ask, is it really safe to

come in

here and let your hair down. You've got a bunch of

strangers

around here. Do you think it's wise for us to come in

here and

share our problems like this? What is going to happen

if

somebody in here wants to tell somebody else? You talk

about it

and you get people to talk about how hard it is to

trust and you

don't demand instantaneous trust. I would tell my

families "you

have no reason whatsoever to trust me. You don't know

me.

You've never seen me so you have no real reason to

trust me. On

the other hand, you really have no good reason to

mistrust me,

I've never done anything to harm you. I'll tell you

what, I am

going to meet you right there with your not trusting me

and your

not mistrusting me. I'm prepared to earn your trust.

If I don't

earn it, don't give it to me.

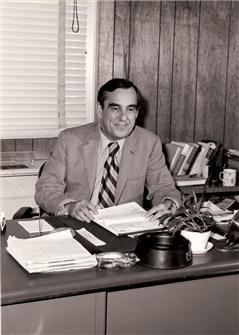

George H. Orvin, MD In His Office

Foster: You made the statement in a workshop that I

attended

once that an adolescent can have a corrective living

experience,

that can bring about significant changes, if they have

one good

relationship.

Orvin: Yes, sometimes they could work through a

horrible

relationship. Some would come in and fight with me. I

had to

know, I had to have a plan of things to do and I had to

provide

corrective living experiences. I had a boy who was

brought to

the hospital who was an abused child. He was fourteen

years of

age, a right husky fellow. He was abused and he was

abusive. He

was failing in school and getting into fights and

attempted

suicide and all sorts of horrible things. The mother

and father

was constantly fighting among themselves. This boy had

a terrible

view of the world and of himself. When I would go to

make rounds

and the nurse was standing there and the nurse was on

the phone

and I spoke to her and she spoke to me and indicated

she would be

right with me. While waiting for her to finish the

phone call,

this boy came walking up and said "Hello, Dr. Orvin".

And I said

"Hello, Jimmy, how are you?" "I'm fine." So he stood

there with

me, the nurse finished her call, hung up the phone,

turned to me

and as she started to say something to me, he

interrupted and she

said "Now wait a minute, Jimmy, Dr. Orvin was here

first. You'll

have to wait until I have talked with him". "Oh, you

g_____

d_____ broads are all alike, you never....". I spun

around and I

stamped my foot and I said "How dare you! Don't you

dare talk to

her like that, young man. Don't you talk to her like

that! I

won't stand for that." He said "Yes" and slinked

away. That was

a corrective living experience. That was the first

time in his

life that an adult male didn't box him in his mouth.

The first

male in his life that was protecting a woman. His

father was

accustomed to pummeling his mother, beating his mother

and his

mother beating him. I saw him an hour later ‑ "Hello,

Jimmy".

"Hello, Dr. Orvin". I was prepared to challenge the

belief in

his mind that this is the way men treat women. This is

the way

men treat children. I knew that he needed that. He

had to come

to an understanding of what that problem is and I was

able to

redefine for him what fathers are like and to suggest

to him that

not all fathers would treat you that way.

Foster: Is it possible that situations like that

could take

place in a multiple family therapy group?

Orvin: Oh, yeah! Oh, absolutely!

Foster: Corrective living experiences.

Orvin: Yessiree. And in the multi‑family group you

get all of

this ‑ there is going to be anger, there is going to be

sadness,

tears, a lot of laughter, a lot of fun. You can learn

a lot.

You want to kind of watch and see who sets by the door

hoping to

be the first one out. You'll want to also watch and

see who sits

by whom. You want to watch and see who won't sit by

whom. I had

a woman and her daughter sitting in the multi‑family

group

waiting for papa to come in. There was a seat on each

side of

them and a seat in between them. He came in and

quickly saw the

two of them sitting there. Went and sat by his

daughter, put his

arm around the back of the daughter's chair and turned

his

backside to his wife. Now, that says something to me.

I saw the

woman's response to that.

Foster: That would be one way to start an interaction

between

the two of them.

Orvin: Oh, I went into it, oh yeah. That was the

first thing

I would do. Before we started I said, "What did that

feel like?"

"What do you mean?" I said, "I saw him and you did

too. He came

in and looked, decided to go and sit by Ellen." She

blushed and

said "Well" and then she was able to talk about that.

He was

then able to give some kind of explanation about it.

The group

was then able to talk about "Well, you know, we need to

have some

things going between ourselves as parents." Children

have a way

of coming in between. The parents are going to provide

you with

rich, rich, clinical material.

Foster: You have trained people to run multiple

family therapy

groups. What were some of the things that you wanted

these

people to know ‑ the therapist, the multi‑family group

leader?

In addition to what you have already talked about, were

there any

other things that you wanted the therapist to know

before they

started leading multiple family therapy groups on their

own?

Orvin: I wanted them to have some understanding of

family

systems. I guess one of the main things I wanted them

to

understand was that it wasn't their group.

Foster: What do you mean?

Orvin: I refer to my multi‑family group ‑ it's not

mine, it's

theirs. It's their group and when I would go into a

multi‑family

group thinking "Now what do I need to talk about

today?" I would

carry with me some sort of a burden that sort of set us

up. I

would go into multi‑ family group and I would go in

before the

group got there. I would go in and I would arrange the

chairs.

I'd do my adolescent groups that way.

Foster: Why did you arrange the chairs?

Orvin: I wanted to impose a degree of order on the

group. I

wanted the time to be effective. I was not there to

play. I

wanted it always in the same room. I wanted the

children to know

it was always at the same time and I wanted them to

know that Dr.

Orvin had taken time to come and get the place arranged

for them.

It said I am thinking about you, I am planning your

recovery. It

imposed a degree of control on the group that might be

seen as

anti‑therapeutic. One cannot handle a sort of rigid

group. One

needs to have some relaxation and one also cannot have

chaos.

Foster: Laquour said there was a schoolteacher type

of multiple

family group therapy leader, a dictator type of leader,

a

lasse‑fare type of leader, and a orchestra conductor

type of

leader.

Orvin: That's right. And sometimes you need to do a

little

bit of each one. I disabuse myself of the belief that

there is

such a thing as co‑therapists. You have two people

doing therapy

but it won't be "co" . One is going to have a little

more

experience than the other. One is going to refer to

the other.

One has a little bit more authority than the other.

Foster: So you don't want to put two director types

together?

Orvin: No. You need to recognize that it's okay. I

had a

lovely lady who worked with me, a Social Worker,

Olivia Riddle,

and she helped me with that group. She and I worked it

together

and we understood the treatment plan and so we would

kind of work

together but I had a way of doing treatment that was

effective

but it was one of several different kinds of

treatment. Now, I

wouldn't for a moment suggest that mine was the way to

do it, but

one of the ways. There are others that are less formal

in their

approach to it. I thought that whatever I did I needed

to be as

much as like me as I could be. You see, as I sit here

today, I

am wearing a three‑piece suit, gold watch chain, cuff

links ‑

that's me. Now, if I were to get down on the floor

with

adolescents, somehow believing that I was going to have

rapport

with them, that I was going to be one of the fellas,

they'd spot

me for a phony. And that's what I'd be. So I caught

myself and

wouldn't let myself do things like that.

Foster: You gave yourself permission to be you.

Orvin: That's right. And for better or worse,

that's what

they've got ‑ they've got me. It could be better in

some ways

but it could be worse in some ways too.

Foster: I've heard some mental health professionals

say that

the key to helping people is to make sure that you're

the best

human being that you can be.

Orvin: That's right and to, somehow or other, come

to terms

with yourself. That is the real big mission in life.

To start

out and find out who we are and to come to terms with

that. In

my book I quote Bobby Burns.

Foster: What's the name of your book?

Orvin: Understanding the Adolescent, published by

American

Psychiatric Association Press. I quoted some of Bobby

Burn's

poetry. One of them has to do with his Ode To A

Louse. He is

sitting in church, Bobby Burn says, and in comes this

lovely,

lovely, beautiful young woman in satin lace. He was a

young man,

noticing pretty young women. And, as fate would have

it, she

comes and sits in the pew right in front of him.

There's the

fragrance of her and he sits there and he is impressed

with her.

Then he is talking about the beauty of her and then he

said "Oh,

suddenly from beneath her bonnet, crept a wee louse."

She was

lousy. She looked pretty, smelled pretty, she wasn't.

And he

said "Oh, what some power the gift of gifts, to see

ourselves as

others see us. Could from many a blunder free us and

even

devotion." We can't see the back of our head. There

are parts

of ourselves that we don't see. Part of the struggle

is to try

to come to know oneself, the good parts and the bad

parts. At

some point in life we begin to review what's happened.

As I look

back on my life at periods I can find events and

aspects, some

that I did not celebrate, things that I wish I'd done

differently. But somehow or another, I had to

recognize that

this is me and I am the product of many, many, many

things. This

is what's left of George Orvin. Recognize it, yeah, I

wish I

hadn't done that, but I did. And to embrace that as

being part

of me because trying to deny it is being sick.

Embracing it and

making it part of me and getting on with my life.

Circumspect in

what I do today because that which I do today, tomorrow

I must

embrace. So we are at that part of our life where we

begin to

come to terms with who we are and what we are

becoming. It is at

a time when a lot of people have adolescent children

that they

begin to do some of that. You haven't always got your

mind on

the adolescent child's needs, sometimes your are

struggling with

yourself, elaborating who I am. Celebrating parts and

maybe

feeling bad about parts but getting on with the process

of

becoming.

Foster: In multiple family group therapy people can

get

glimpses of themselves.

Orvin: That's right.

Foster: And the therapist who can share his or

herself with

that group is in actuality sharing a process that they

can

emulate.

Orvin: Completely. And while I am reviewing myself,

I must

stop and recognize the context in which those things

took place.

Bobby Burns also has another one An Ode to a Mouse

and he's a

farmer and he's out plowing and inadvertently turns

over a nest

of field mice. He stops and speaks to the mouse and

he's

apologizing for tearing up his home. He points out to

the mouse

that sometimes things, things of mice and men, don't

always turn

out the way we want them to and that we need to

recognize that

and come to terms with the fact that the best laid

plans of both

mice and men often go astray. That's because we are

human, by

being human we have the advantage over the mouse. We

can reflect

on our past, visualize our future, prepare ourselves

for our

future, come to terms with our past and have an

understanding of

who we are and what we are.

Foster: The mouse has to take some responsibility for

having a

destroyed house too.

Orvin: That's right and Burns lets him know that.

Foster: The closing of a multiple family therapy

group. An

hour (hour and a half) has gone by, someone is in

tears, what do

you do?

Orvin: I think it's right tacky to get up and leave

a wound

unsewed. They're always ripped up and they are always

sewed back

together. So I think it's important to try to do

something

around helping that individual at that particular

juncture.

Sometimes it's not necessary that the whole group stay

on.

Almost invariably somebody has to leave. And that may

be a good

time to do some individual stuff anyhow.

Foster: If this person has consistently waited until

five

minutes before the group is to end to do any work,

would

encouraging them to wait to do their group work at the

next

session be acceptable?

Orvin: Yes, and what you want to do is try to

understand and

talk to them a little bit about how scary this must be

and that

by waiting until almost the end maybe you are afraid

that once

you got started you couldn't handle it. Maybe you are

afraid

that people would jump on your body. Talk about that a

little

bit.

Foster: They can come back next week and start

dealing with

these feelings.

Orvin: That's right.

Foster: Will you talk about the individual growth

experience of

each person in the family, as well as the growth of the

family?

Orvin: That is what I like to call a process of

becoming that

all of us experience. It begins with creation. It is

a process

that goes on, it's psycho logic, sociologic, biologic,

theologic,

educational, and we roll in that process when we are in

the

process of becoming, and we are going to become what we

are going

to become. When you see someone like me, I have

become. I have

reached a point in my life where I've probably done as

much

growing as I am supposed to do. I've sort of gone by

the way of

"What you see is what you get and it won't get any

better".

Maybe it will get worse but certainly no better. That

process is

going on. You are in the process of turning out.

Someday you

are going to reach the end point of all of this psycho

logic,

sociologic growing that you are now doing. You are

going to

become who it is you will eventually become. Knowing

that that

is going on has helped me to be amused at times as I

view my

own growth, but certainly contemplative and thoughtful

about what

is happening and what impact is this event going to

have on me.

Foster: Amused?

Orvin: Yeah ‑ tickled and entertained by what's

happening to

me, then to be objective about that. We struggle

through life.

My good clergyman, Sam Cobb, my Rector in Saint

Phillips

Episcopal Church, said to me, "George, in the

existential

experience which we call life we seem eternally trapped

between

what we should do and doing what we must". It is a

struggle, we

are working our way through life, problem‑solving and

learning.

All those events have some influence on how the process

is

progressing. You need to sort of have an understanding

of what's

happened with that adolescent. You need to know that

there are

parts of life where each of us face specific sorts of

challenges.

Pretty much, commonly so, in all human beings. The

adolescent,

at age twelve to thirteen, begins to develop into an

adult. He

wants to become an adult. That is part of it. The

other part

that is just as tough is that while they are becoming

an adult,

they stop being a child. You are going to stop being a

child.

You and I are working as helpless and sometimes stumble

to help

the adolescent. If we, somehow or other, don't

recognize that he

is trying to become an adult, he's offended. If,

somehow or

other, we treat him as if he is still a child, he is

outraged.

In fact, he will do things to his own disadvantage to

prove to

you that you can't make me ‑ so there. He is

struggling to

become an adult, but struggling even harder to stop

being a

child. What he has to do at age thirteen and twelve is

about

three major roles. You have to start thinking about

your parents

differently. You have to stop seeing them as

mythologic giants

so that you can stop thinking of yourself as a helpless

little

child. One of the ways that you stop thinking about

your parents

as giants is to cut them down to size. Cut their legs

off and

show them they can't make you do anything you don't

want to do.

Adolescents run into problems doing that. Thirty‑five

to forty

year old people run into problems when it's happening

to them

through one of their children. They have this child

who tries to

de‑mythologize his parent and here's the parent ‑

what's

happening to him? He too is struggling. What happens

to people

around age forty? You begin to add up the score. You

begin to

recognize that there are probably fewer tomorrow’s than

there are

yesterdays. You begin to come to terms with your

dreams, your

hopes, your ambitions. Your options narrow, narrow,

narrow. So

that when that adolescent is struggling to disabuse

himself of

this view of his wonderful, all powerful parents, this

puts them

into their own problems that they have. A

forty-year-old mother

is undergoing some changes. Her role in life is

changing. Her

reproductivity is about to come to an end when all of a

sudden,

right under her nose, the reproductivity of her

fourteen year old

daughter blossoms. Most mothers celebrate that

development in

the child.

Foster: That's one of the few rights of passages that

we have

in this society.

Orvin: That's right, but it says something to mother

and the

contract stings a little bit. As she sees the

beginning of

creative capacity in this child, it reminds her that

hers' is on

the wane. You see, those are things that are part of

this

process of becoming. Those are the sort of things that

influence

the psychological stylus and anonymity of parents as

children are

struggling to become adults. So we have to change

their view of

their parents and they have to think about who they

are. There

is this young adolescent who struggles to thrash out

some sort of

identity of what sort of person we are. Thirdly, we

have to find

out what it's like to be a man and to be a woman. We

have to

sort of evolve in gender ‑ the identity ‑ the

genderness. All of

that creates ferment within the family system.

Depending on how

well those two adults are getting along. Depending on

how well

they comprehend what's happening and depending on their

own

psycho logic intactness, they want to respond to what

this

adolescent child is trying to do and they are either

going to

help it or hinder it. So that when you and I see our

adolescent

struggling with some sort of difficulty do we scratch

our heads

and wonder what is it that is happening to this child?

We will

always be in trouble until we find out what else is

happening at

home. Get a hold of that family. So I have these

children that I

was treating, I said to the parents "You must come and

help me ‑

you have to take part". Well, Dr. Orvin, he's really

the problem

‑ we want to do whatever we can to help him. And my

position has

always been "You can't do that ‑ you've gotta help me

help

somebody you love". I would DEMAND that the family

come.

Foster: So, if my son is with you and I didn't come

for the

admission, would you pick up the phone and give me a

call?

Orvin: Well, I'll tell you what -‑ I wouldn't

evaluate him.

Foster: Okay, so parents would have to be there.

Orvin: I wouldn't evaluate him. If you are not that

worried

about him, neither am I. That sounds sort of callused

but I

think in some ways we become ambiguous about what we

tell our

families because I think some of us understand that we

really

ought to have the family involved but we aren't afraid

they won't

come, we are afraid they will. Then what am I going to

do? How

am I going to manage these. I don't know. So we

collude on an

unconscious level to avoid the parents and avoid the

family.

When the family says "Well, I can't make it on

Fridays" ‑ well,

all right, we'll do the best we can without you then.

Which

really gives us an excuse for failing and when we fail

it's going

to be your fault because you didn't come. But we

really collude

in that and I think, up front, one needs to be able to

say ‑ tell

you what, if you are not interested in coming, some

people come

too soon, some people come too late, but some come too

soon and

you folks aren't ready for help yet. When you are

ready, get in

touch with me. There has to be some understanding that

if you

are going to allow illness to remain encapsulated

within the

family system, you are not going to produce health in

any other

part. I have seen healthy individuals live in families

that were

maladaptive and dysfunctional but it is virtually

impossible to

really take the young adolescent and treat him without

some sort

of participation by family.

Foster: If an adolescent were to come to treatment

and get

help, would that make any difference in this child's

life if the

parent's wouldn't come?

Orvin: Well, it might. You know, in some ways we

sometimes

strike up deals that we don't particularly like and

sometimes you

end up doing the best you can. I think in some ways,

we are

accustomed to saying "Those people don't care about

their

children -‑ those people don't care about their

children". Now,

I've dealt with all five socio‑economic classes -‑ the

richest and

the poorest, the least educated and the PhD's and the

MD’s.

I've dealt with the full spectrum and I have found that

a lot of

times the folks who have a severely dysfunctional child

are doing

about the best they can. What happens is that child

gets into

some sort of trouble, the police get him and take him

home and

knock on the door and get mama and say "Here, we caught

him

breaking windows, throwing rocks at cars. Make him

stop -‑ do something".

Do what? This poor woman, nine chances out of ten, is

madly treading

water with her nose just above the surface.

Foster: Working to survive.

Orvin: The last thing she needs is one more wave.

And

somebody brings the child and says do something and she

says do

what? We don't know, but do something. There and

again, my

experience was when I would say to that mother "You are

and you

will come because I am going to help you ‑ I am going

to help you

and I am going to help your child ‑ there is hope ‑

something can

be done and things will get better". That man or that

woman will

breathe a sigh of relief. Finally, somebody is going

to help me.

I think we need to have some sort of understanding. I

think that

all parents love their children. All parents love

their

children. They can't help it. Now, not all parents

are good

parents. Sometimes loving them isn't enough. You are

using it

as an excuse too when you could do some other things.

But it

must be taken as a given. This child’s' parents are

not really

trying to make his life miserable. They really aren't

trying to

make things worse. They may be doing that, but it

usually is

because they think the wrong thing is the right thing.

Foster: It's not what they don't know that causes

problems,

it's what they know that is not true.

Orvin: That is true, and then it is easy to do the

right

thing. When the choice is between doing the right

thing and the

wrong thing, we'll all do the right thing. But what do

you do

when the choice is between the wrong thing and the

wrong thing?

Then what do you do? You do the best you can in life.

Foster: An example of that might be the struggle that

parents

are having today with adolescents who smoke cigarettes.

Orvin: Certainly. Or doing some of the other things

that they

are doing. You are limited as to what you can do if

you've got

all the skills. Life deals us a hand of cards. Those

hands

aren't always Ace, Kings, Queens and Jacks. For a lot

of folks,

that hand had some Twos and Threes and a couple of

Jokers.

That's the hand they've got and that's the hand they've

got to

play. I've had people who just didn't have a high

education and,

boy, they were doing the best they could. They were

making some

bad mistakes. There are people who have maybe ill

health or a

number of problems that they have but almost all of

them, ALMOST

ALL OF THEM, are trying.

Foster: What about the adolescent who doesn't have a

parent or

a myth to overcome?

Orvin: I think almost every child has somebody ‑ has

a

something. If you look and if you be creative and

innovative

about that, I would always insist that the child’s'

family come

and take part. Sometimes there was no family but I

almost always

found a Social Worker that liked this child in

particular or an

uncle or an aunt or a grandmother or grandfather. And

if I

worked at it, I could get somebody who would come and

be an

advocate for this child. It wasn't a mama or a daddy,

but an

advocate.

Foster: Do we move from one myth to the next myth?

Orvin: I think what we need very much to try to

foster a

better impression of who we are and what we are with

ourselves.

When we start in life, we are at the mercy of fate and

the

elements. If we leave a child on the shelf somewhere

for two

weeks, when we go back, that child is going to be

dead. A child

needs immediate care because it is so vulnerable. That

child, as

it begins to develop some sense of the world around

them, needs

to believe that he has some protection. Somebody cares

enough to

take care of me. If that infant or that little child

really

understood how dangerous this world was and how

vulnerable he is

or she is, no psycho logic growth could take place. The

child

would spend its time in constant terror. So, the human

mind is a

wonderful instrument. It projects on to these people

called

parents, power and knowledge that no human being could

possibly

possess. My dad's the strongest man in the world, my

dad can

beat your dad, my mom is the most wonderful woman in

the world,

she won't let anything happen to me. Those are the

things we

need to believe so that we can go blissfully about the

business

of being a child.

Foster: If we believe the system has power, then the

system has

power?

Orvin: That's right. But when we reach adolescence

we begin

to become an adult and if we grow into adulthood

believing that

mama and daddy are these mythologic giants, then we are

going to

continue to believe that we are helpless, vulnerable,

little

weaklings. So, we have to disabuse ourselves of the

belief that

mom and dad are all‑powerful so that we can get rid of

the belief

that we are totally helpless. So, you see, it's

shrugging off an

encumbrance.

Foster: It's shedding a system of denial?

Orvin: Well, yes! It's a matter of beginning to no

longer

need external security. Beginning to provide our own

security in

preparation for ultimately becoming a provider of

security for

others. The trip from consumer of security to provider

of

security is neither quick, smooth, nor direct. That is

part of

the process of becoming an adult. Shedding this belief

that

somehow or other I am helpless.

Foster: We move from dependency to interdependence.

Orvin: That's right. We must begin to surrender

that

dependence. We finally surrender, I think, that last

little bit

of symbolic dependence when our last parent dies.

Foster: When we become an orphan.

Orvin: I had a forty‑five-year-old lady say to me

her mother

just died and she said for the first time in my life I

am no

longer somebody's little girl. You become an adult.

So that's

part of what that adolescent is doing ‑ is beginning to

take onto

himself a view of himself as competent and capable of

taking care

of himself and to be able to do that he must get rid of

some

childish beliefs. When he begins to shed this

encumbrance, it's

helpful if those who have been providing him with his

protection

understand what's happening and permit it and, if

possible, even

help it. At least try to not absolutely thwart it.

Foster: Are you saying be careful what battles you

choose to

win with your adolescents?

Orvin: Or to fight, yes. Let me go one step

further. The

parent is going to respond to that threat of disruption

because

when that first child leaves that's the first harbinger

of the

ultimate death of the family. Families get born,

families have a

childhood, families have an adolescence, families

mature,

families grow up, and families die.

Foster: Parents get divorced and families die there

too.

Orvin: That's true. So that as that adolescent

begins to

struggle against the ties of the family those parents

need to

understand what is happening. And then will respond to

his

efforts depending on what's happening between the two

of them.

If there is one thing a parent can do to insure some

sort of

psycho logic health for their child, it isn't so much

what you

tell them to do and not do, what matters most of all is

how you

and I, as a man and a woman, as a mother and a father,

treat one

another.

Foster: The most important relationship in a family

is the

husband and wife relationship.

Orvin: Exactly right. We begin to deceive and to

portray on

children when first we believe that the parent/child

relationship

transcends the husband and wife. That's the foundation

of THE

FAMILY. That's what is going to help this child get

through,

because, you see the man and the woman they come

together and

they put two processes of becoming, together. Each is

influenced

by the other. My wife has influenced how I have turned

out. I

have influenced how she has turned out. But each of us

has been

in the process of turning out and becoming whatever it

is we are

going to become. At least two processes of becoming

are

happening. One of the things that influences those

processes is

the introduction of a child into that family system.

If the two

parents can meet the needs of each other, children will

prosper

more. For when one parent fails to meet the needs of

the other,

that parent reaches across the generational boundary

and involves

himself or herself in a need relationship with one of

the

children. If that relationship is the only thing

mother has

going, if she no longer feels valued as a woman and as

a wife and

all she has got left is mother, she is going to be

loathing to

give it up quickly or easily. As that child begins to

move away

from home, that really means the end of a meaningful

fulfilling

relationship. Unwittingly and unknowingly, mother

might very

well thwart this child's moving into autonomy, not

understanding

why. That happens to us infrequently if that woman is

valued as

an individual, is valued as a woman, is valued as a

wife, and

valued as a mother. And sometimes being mother feels

so good

that women tend to discount the value of just being a

human

being, the value of being a special kind of human being

‑ of

being a female human being, and the special value of

being a

wife.

Foster: If a mother gets caught in that role and

doesn't

develop other relationships, and other roles in her

life, then

when it comes time for the kids to be launched from

home, it is

more difficult.

Orvin: It is more difficult.

Foster: Is it possible that the kids will stay home,

or return

home, so that mom will have meaning and definition to

her life?

Orvin: Yes, and mother won't do that intentionally

or

knowingly. She won't want to cripple the children.

But that

does happen and it happens to good people that don't

understand

what is happening.

Foster: If mom is really dependent on that one role

in her

life, her marital relationship hasn't been nurtured?

Orvin: Absolutely, so one of the first things I can

do to help

the adolescent is to get that child’s' mother and

father to like

one another. I've never had to testify in a custody

case where

the child’s' parents took care of one another.

Foster: How do you get mothers and fathers to like

each other

as husband and wife?

Orvin: Gradually, cautiously, skillfully, and most

of all,

understandingly. First of all you've got to really

believe that

somehow or other that it is a valuable relationship. I

have seen

marriages fail and I've seen marriages die because of

divorce or

death and I have seen a family raised by one parent and

that one

parent doing a marvelous job. But somehow or other,

that parent

has to be able to find something in his life or her

life that

helps them feel good about themselves so that they

aren't totally

dependent on that child’s presence in order to continue

feeling

good about themselves. I want those folks, the single

mother,

single father, or married couple, to find some meaning

in their

lives.

Foster: As long as mom is that attached to the

daughter, she is

in the middle of a process addiction, she doesn't

really have

contact with who she is and so the objective might be

to get her

to look inward at herself and begin to discover the

unique human

that she is and love herself.

Orvin: And to value herself. Put some value on

herself. You

know, the one thing worse than self‑love is self‑hate.

Something

we need, but not be narcissistic about ourselves. I think

we need

to have some value for ourselves, some respect of

ourselves.

Foster: I have come to know that we learn to like

ourselves

based on the feedback as seen through the eyes of others.

Orvin: Yes.

Foster: Other's reactions to my personality is important

to my

knowing who I am.

Orvin: Yes, that makes us a social being.

END

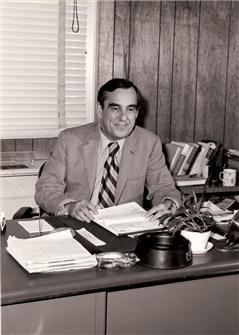

A young George H. Orvin

Return to Homepage